Exploring Pensioners’ Lives

By Kirsty Walker, Archive Volunteer

[O]ur friends of an hour whom we have endeavoured to describe just as they are, and amid the surroundings of their daily lives. i

William Scriven, 1900

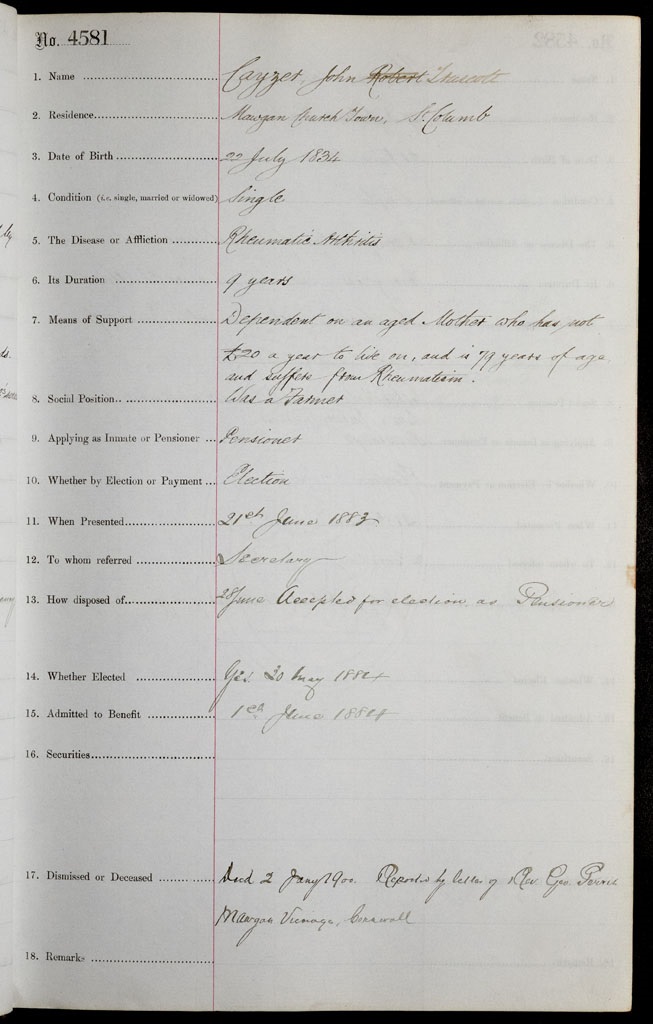

How much do we know about the lives of the RHN pensioners at the end of the 19th century? Over the past year, I have been transcribing an admissions case book containing detailed information about every candidate who applied for admission to the hospital. The majority of successful applicants were appointed as out-patients or ‘pensioners’ and given an annual sum of money for the rest of their lives. While the case books tell us a lot of information, from a candidate’s full name, address, and date of birth, to details of their medical conditions and means of financial support, they can only capture a snapshot in time. What happened to the hospital’s pensioners in the years that followed?

With a little help from the RHN archives, we can start to answer this question. In the 1890s, a writer called William Scriven travelled across England to meet some of the hundreds of pensioners supported by the hospital. His firsthand accounts were published as a fundraising appeal, but they also provide a poignant glimpse into the pensioners’ daily lives.

Figure 1: Admissions record for John Truscott Cayzer. ii

In the summer of 1897 Scriven’s journeys brought him to the home of John Truscott Cayzer in Mawgan, Cornwall. The Cayzer family name had deep roots in Cornwall, where several generations had worked in agriculture. John Cayzer had taken over his father’s farm and at one time had farmed 20 acres of land.iii But by 1883, his health had declined and he was unable to continue working. He lived with his elderly mother who had an income of less than £20 a year and was herself in poor health. At the age of 48, he applied to become a pensioner of the hospital, having suffered from rheumatic arthritis for nine years.

The 19th century saw a shift in medical understandings of rheumatoid arthritis. Before 1800, it was not clearly differentiated from other joint conditions like gout, but by the 1880s physicians identified the painful, chronic and progressive nature of the disease, and its characteristic inflammation of joints, painful swelling and stiffness in the fingers, wrists, feet and ankles. Treatments such as splinting of affected joints, cold therapy and hot water baths focused on relieving pain and reducing inflammation. However, understandings of its causes and the development of effective treatments would not arrive until later in the 20th century. iv

By the time Scriven interviewed John Cayzer 14 years after his application, much had changed. “We saw before us”, writes Scriven, a man “doubled up rather than sitting in a chair fitted with wheels. Years of acute suffering have wasted his limbs and written their record on his face”.v An illustration shows John Cayzer sitting in a chair, his legs covered by a blanket, and a crutch propped up against the wall. Scriven described him as an emaciated figure after suffering for 24 years, noting that he could no longer stand without assistance.

Figure 2: ‘J.T.C’. vi

John Cayzer’s mother, Fanny, had died in 1891 at the age of 85.vii He was cared for by his former dairy maid, Ann. As the pension from the hospital was his only income, he could not afford to pay her wages, and she was forced to rely on a small annual donation by friends to buy clothes. During Scriven’s visit she confessed tearfully that she would not be able to care for him for much longer due to her own poor health. Scriven recorded an emotional exchange between them:

“But you went away once Ann.” “Doan’t you say nothing about that,” she angrily retorted; “I came back again, I did, for I was that miserable knowing he’d nobody as knowed how to wait on ‘un proper like – but he did aggravate me, that he did – but he won’t do it again, he’s promised me.”viii

They explained that Ann had once left him because of a disagreement about a poem he had written about her. However, after a short separation she returned, steadfast in her dedication to his care.

Two years after Scriven’s visit, John Cayzer died at the age of 65. Scriven’s descriptions paint an extraordinary portrait of his experiences of illness and care in the final years of his life. Exploring the stories of John Cayzer and other pensioners, we gain a profound insight into the challenges facing people living with disabilities in 19th century England and the crucial role institutions like the RHN played in their lives.

i William Scriven, Friends of an hour (London, 1900), p. 50.

ii Case Book Volume 7, 1883-1888, RHN Archive, GB 3544 RHN-AD-02-01-7-0137.

iii 1881 Census of England, Civil Parish of St. Columb Minor, Eccl. District of, Folio 42, p. 16.

iv David Scott, ‘The history of rheumatoid arthritis’, in Oxford Textbook of Rheumatoid Arthritis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020), pp. 3-12.

v William Scriven, Feeble Folk: Notes of a Ramble in the West of England (London, 1899), p. 17.

vi Scriven, Feeble Folk, p. 18.

vii England and Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915, Volume 5C, p. 33.