A “Most Exceptional Case” – a mystery from our archives

A “Most Exceptional Case” – a mystery from our archives

Written by Dr Sarah E Hayward, freelance historical researcher and heritage assistant, and volunteer at the RHN archives.

There are occasions when a historical researcher or archivist gets to play detective. Solving mysteries can be very seductive, and the potential to untangle mysteries that others have failed to resolve is particularly alluring. Surely, one thinks to oneself, the answer must be here amidst all of this paper ephemera! If I just look long and hard enough, I’ll be the one to uncover that single, vital piece of evidence that everybody else has somehow overlooked.

We have a 137-year old unresolved mystery to offer you today, involving one of the most well-known figures of the late nineteenth century. Its source is an open letter from Francis Carr-Gomm, then Chairman of the London Hospital, published in The Times newspaper on the 4th of December 1886.

His letter read:

-

To the Editor of The Times

Sir, I am authorized to ask your powerful assistance in bringing to the notice of the public the following most exceptional case. There is now in a little room off one of our attic wards a man named Joseph Merrick, aged about 27, a native of Leicester, so dreadful a sight that he is unable even to come out by daylight to the garden. He has been called “the elephant man” on account of his terrible deformity…

When he reached the London Hospital he had only the clothes in which he stood. He has been taken in by our hospital, though there is, unfortunately, no hope of his cure, and the question now arises what is to be done with him in the future. He has the greatest horror of the workhouse, nor is it possible, indeed, to send him into any place where he could not insure privacy, since his appearance is such that all shrink from him. The Royal Hospital for Incurables and the British Home for Incurables both decline to take him in, even if sufficient funds were forthcoming to pay for him… and the difficult question therefore remains what is to be done for him.

Terrible though his appearance is, so terrible indeed that women and nervous persons fly in terror from the sight of him, and that he is debarred from seeking to earn his livelihood in an ordinary way, yet he is superior in intelligence, can read and write, is quiet, gentle, not to say even refined in his mind… Can any of your readers suggest to me some fitting place where he can be received?

F.C. Carr-Gomm, ‘The Elephant Man’ The Times, 4th December 1886

Fig. 1: Right profile of Joseph Merrick (‘Elephant Man’) from the Wellcome Collection

We’re left, then, with unanswered questions and room for speculation:

- Did Francis Carr-Gomm approach us with an official request regarding Joseph Merrick? If he did, why was Merrick turned down by the Hospital? And why is there no evidence of this application in our archives?

- Might Carr-Gomm instead have approached somebody at the Hospital with an unofficial enquiry (and maybe the reply was that Merrick would most assuredly not be admitted)?

- And if Carr-Gomm didn’t do either of the above, why would he specifically refer to it in his open letter?

According to G C Cook, author of Victorian Incurables. A History of The Royal Hospital for Neuro-Disability, Putney, “It seems most likely that [Merrick] was either considered to belong to the ‘pauper class’, and hence a responsibility of the workhouse and not the RHI, or that his appearance was so revolting that he would have been unacceptable on those grounds.” (Cook, 2004, p.179)

Whatever the reason behind Carr-Gomm’s claim, it had a dramatic effect. A media frenzy erupted, and money and gifts flooded in from all over the country. Thanks to these funds, Merrick was able to stay on at the London Hospital, in what Carr-Gomm described as “the little room under the roof”. Merrick died there just a few years later in April 1890.

We’re still left, then, with our mystery, the answer to which may yet lie within our own archives, or elsewhere entirely. And that’s just par for the course in archival research.

Archive of the Month

To tempt you with our enticing archives, we will be showcasing an item from our collections each month. This month, we’re honouring the Explore Your Archive theme for July – SPACE – with an aerial photograph of the Hospital taken in the 1960s, and by looking at the evolution of our site here in Putney.

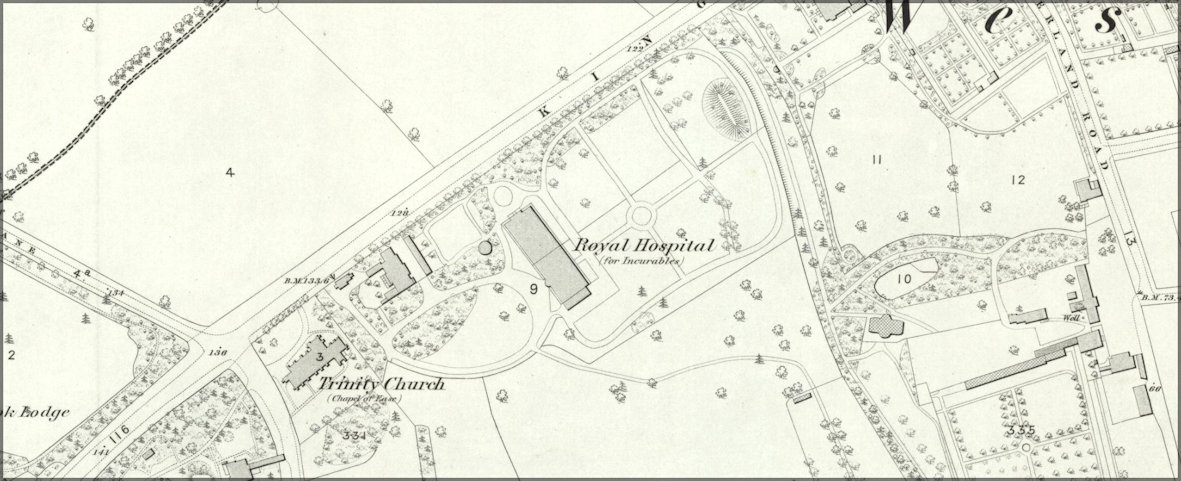

We begin a hundred years earlier, in the 1860s, when the Royal Hospital for Incurables (as the RHN was then known) first moved into Melrose Hall, an elegant mansion built in the late eighteenth century. At the time, its 25 acres of grounds encompassed landscaped gardens designed by Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, a working farm, and an orchard and market garden.

Fig. 2: London LXXIII. Surveyed: 1865 to 1866, Published: 1871

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

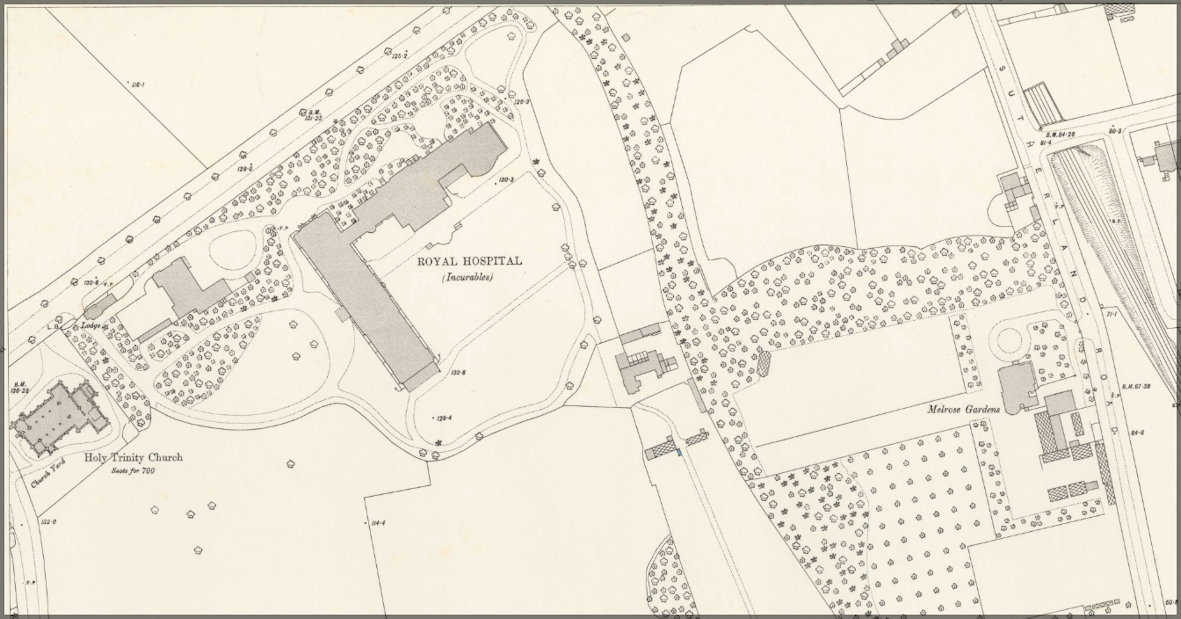

A number of necessary expansions to the building soon followed, annexed to the original building which still sits at the heart of the Hospital. Of particular note was the ‘Great Extension’ of 1879, an entire new wing whose façade ran parallel to the main road. With accommodation for an extra 100 patients, this also provided light and spacious new communal areas; kitchens and a dining room; much-needed additional storage; and basement level accommodation space for staff.

Fig. 3: London X.77. Revised: 1893, Published: 1895

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

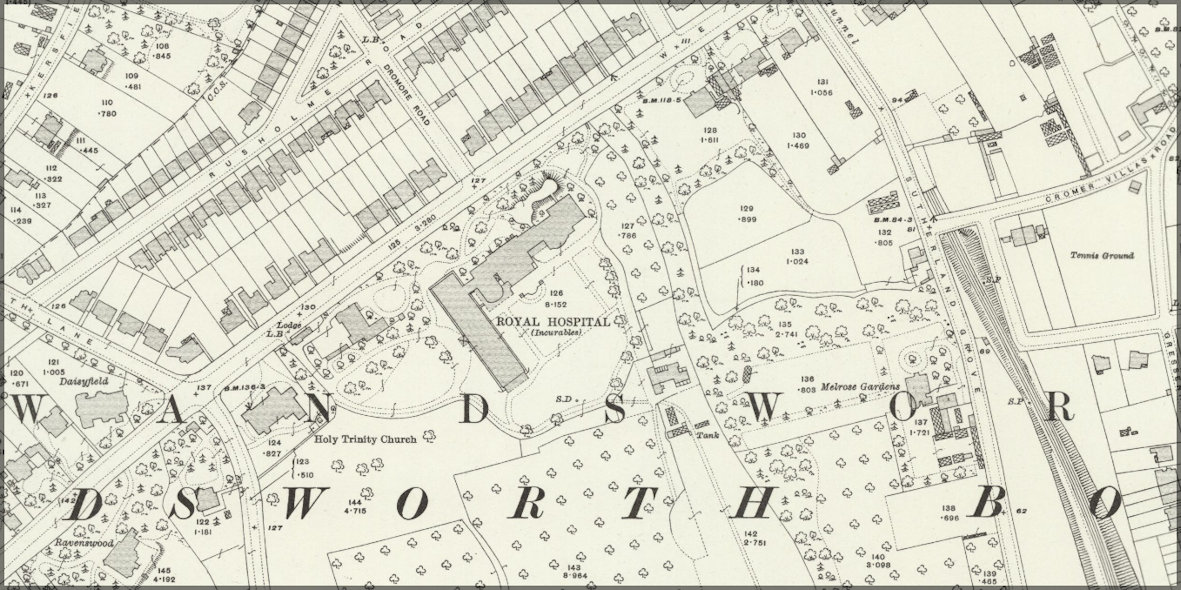

By the turn of the new century, the provision of fresh milk had been outsourced to the Dairy Supply Co., and in 1931 the House Committee decided to also phase out pigs and poultry, marking the end of livestock on the farm. The vegetable garden survived and continued to be cultivated, alongside the now thriving orchard.

In 1909, electric lifts were installed, replacing the existing hydraulic lifts (which had themselves replaced the original hand-operated ones).

Fig. 4: London VIII.11. Revised: 1913, Published: 1916

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

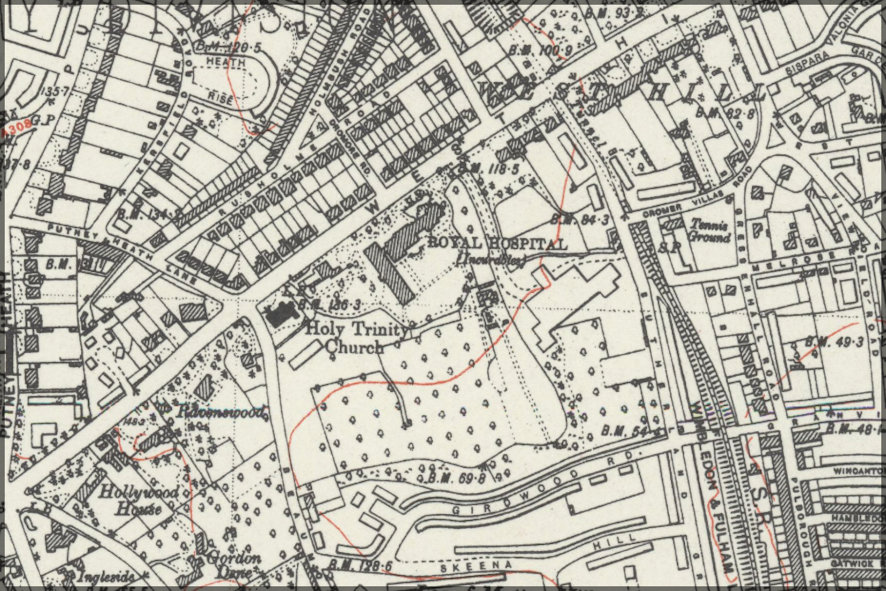

In 1935, the Duchess of York (the late Queen Mother) opened a new block of accommodation for the nurses (who had until then resided within the main building) behind Holy Trinity Church on the western edge of the site.

Fig. 5: London Sheet N. Revised: 1938, Published: ca. 1946

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

As you can see from the map above (from 1946) and the aerial photograph from our archive collection below (taken in the 1960s), the site changed very little over these two decades.

Fig. 6: RHN.PH-01-04-0001, Circa 1960s

The subsequent half century would see the Hospital’s site shrink even further in the wake of redevelopment. It now sits on a busy main trunk road into the Capital, closely surrounded by the expanded urban city of London. And yet, the eighteenth century Melrose Hall still survives – it is now the main reception area which welcomes visitors to the RHN. The architectural splendour of the nineteenth century ‘Great Extension’ wing remains largely unchanged, most notably the Assembly Room – complete with restored stained glass windows – and the De Lancey Lowe Room. Most importantly, we proudly continue our 169 year legacy (and counting) of providing support, rehabilitation, and care for people with complex disabilities.

Fig. 7: Google Maps Terrain View, 2023

Bluesky, Getmapping plc, Infoterra Ltd & Bluesky, Maxar Technologies,

The GeoInformation Group

Written by Dr Sarah E Hayward, freelance historical researcher and heritage assistant, and volunteer at the RHN archives.